Designing the Next Gen LEGO® Sorting Machine

Sorter V2 is upon us

Version 1 of the LEGO® sorting machine worked. Kind of.

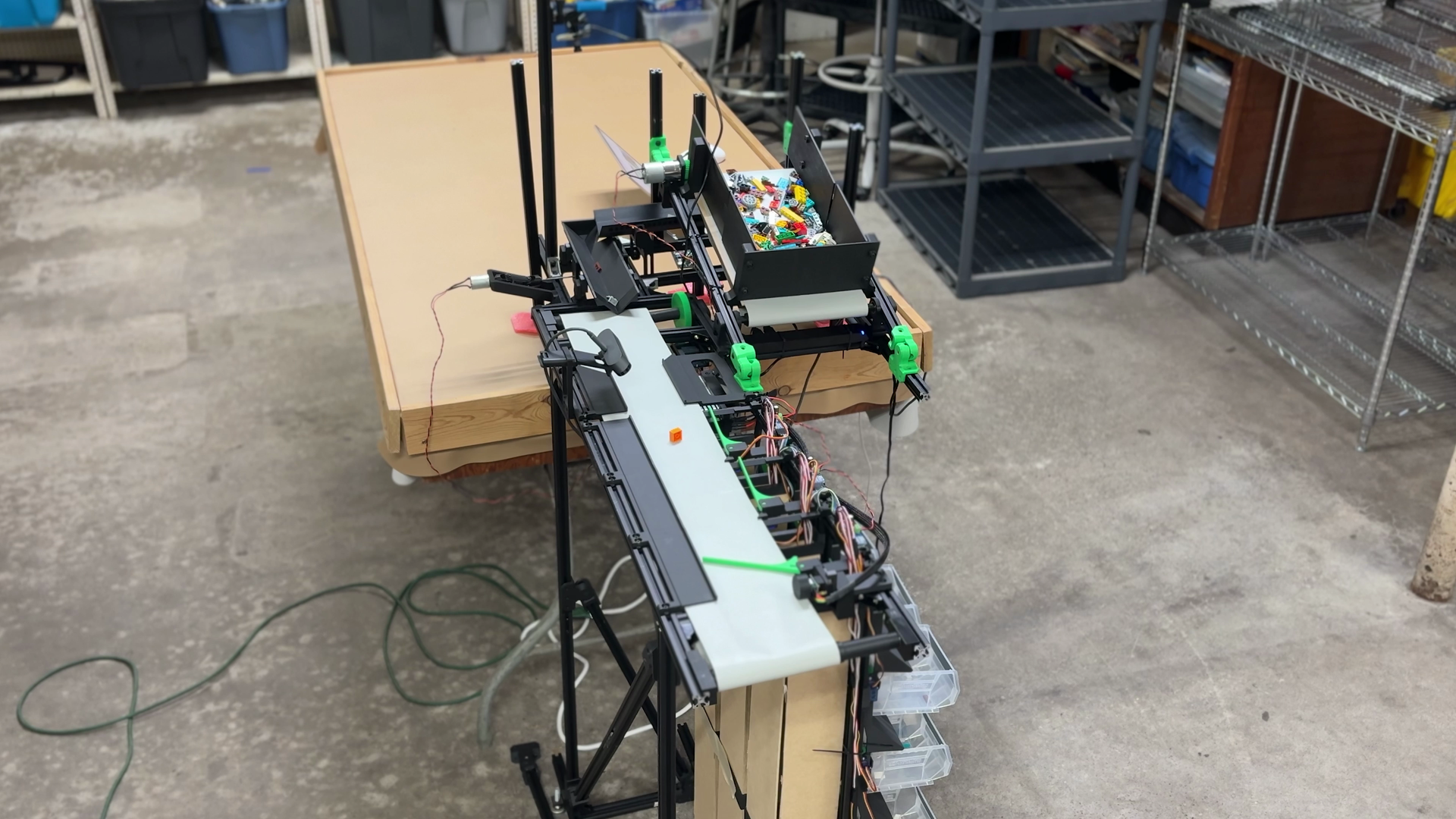

It was complex, slow, difficult to assemble, and parts literally snapped if it ran long enough. Sorter V1 had a few requirements: 3D printed materials, and extensibility. The long-term goal is to sort a million pounds of LEGO®, not with the biggest, bestest, fastest machine, but by multiplying throughput with many cheap machines.

Sorter V2 is upon us. It inherits those requirements and adds a critical one: other people need to be able to build it. A project like this lives and dies by complexity. We've been exploring the design space to reduce V1's complexity to the minimum needed to put LEGO® pieces into modular bins.

Refresher

For an overview of Sorter V1 and the general concepts used when building a LEGO® sorting machine, I recommend you check out this video. As a reminder, the process can generally be broken into three steps:

- The feeder, which takes a bucket of LEGO® pieces and dispenses just one at a time

- Classification, which identifies the LEGO® piece

- Distribution, which puts it into some specific bin from a large array of bins

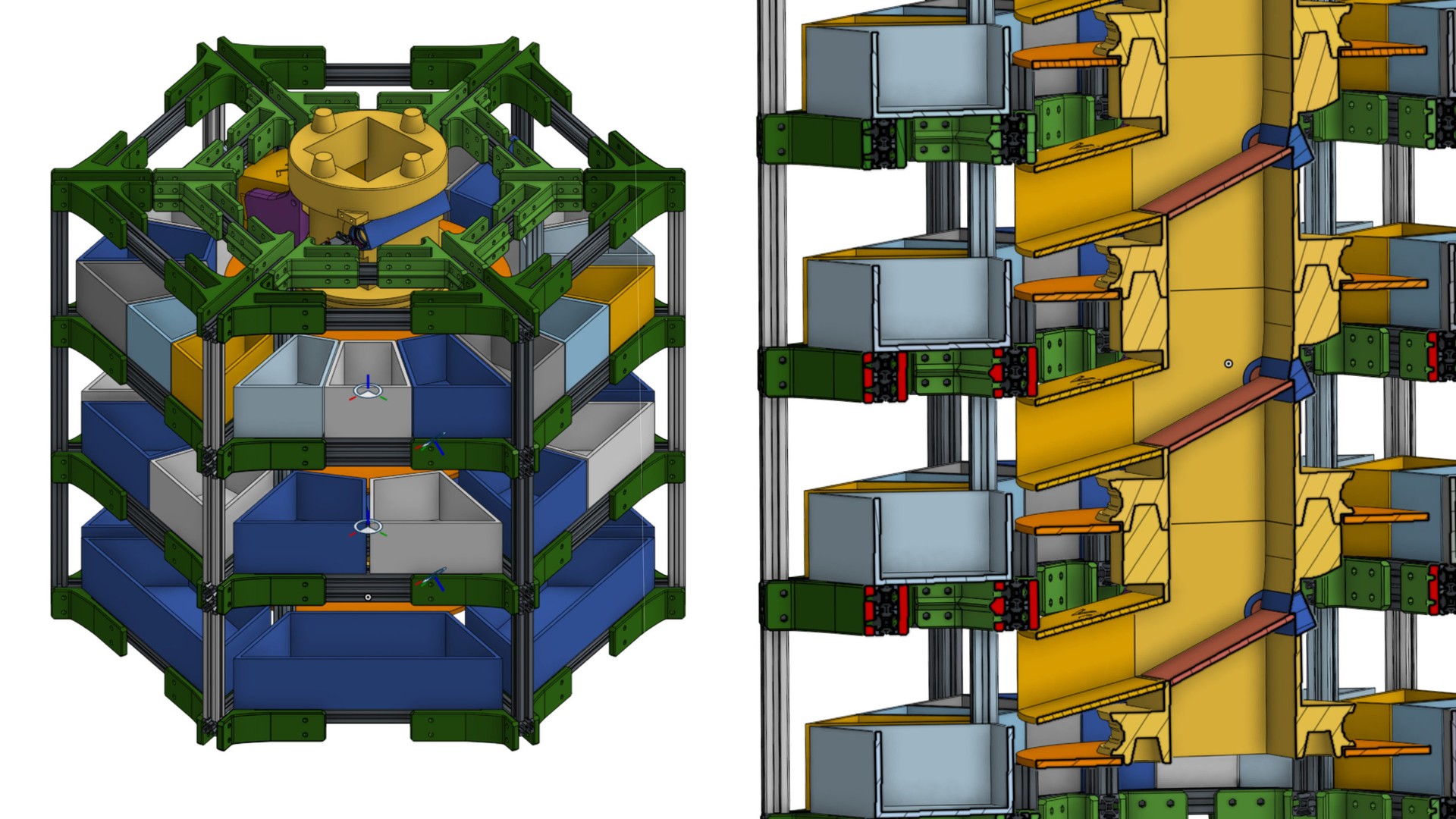

The Pancake Stack

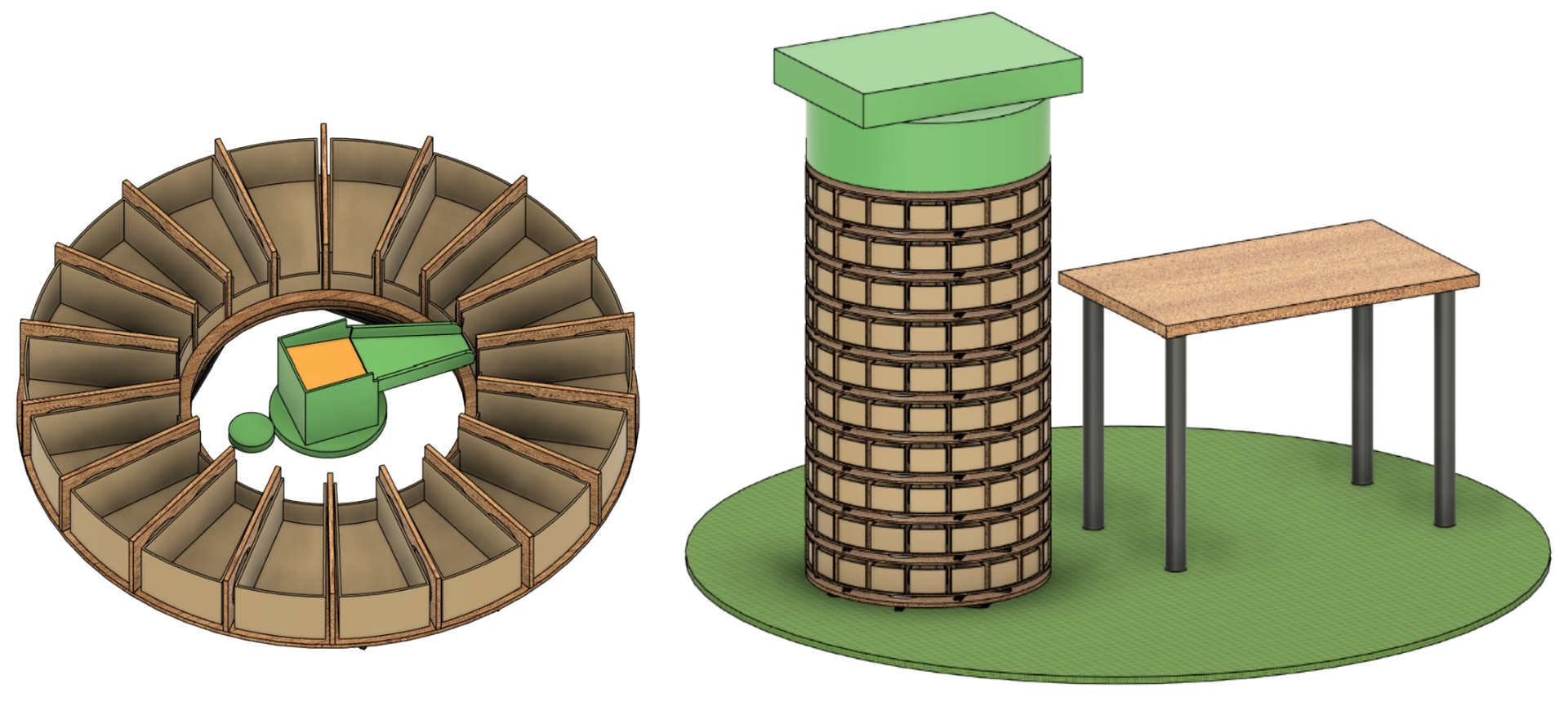

In V1, I ruled out circular bin arrays because they didn't seem modular. That's when Nikola Totev, a key contributor and the project lead for the distribution system, came along to prove me wrong.

The idea came to him through a stack of pancakes. What if we took the chute concept from V1 and combined it with the circles?

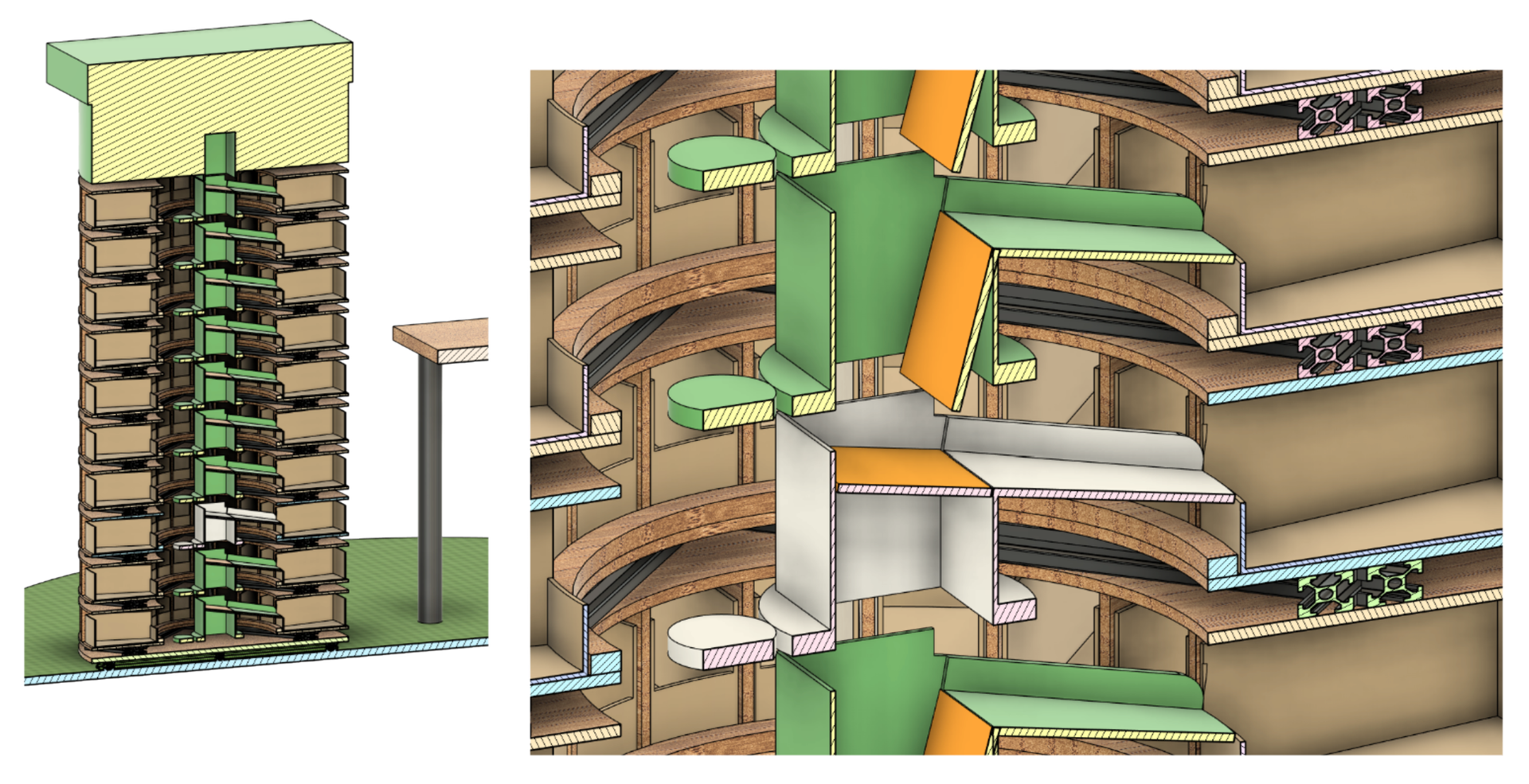

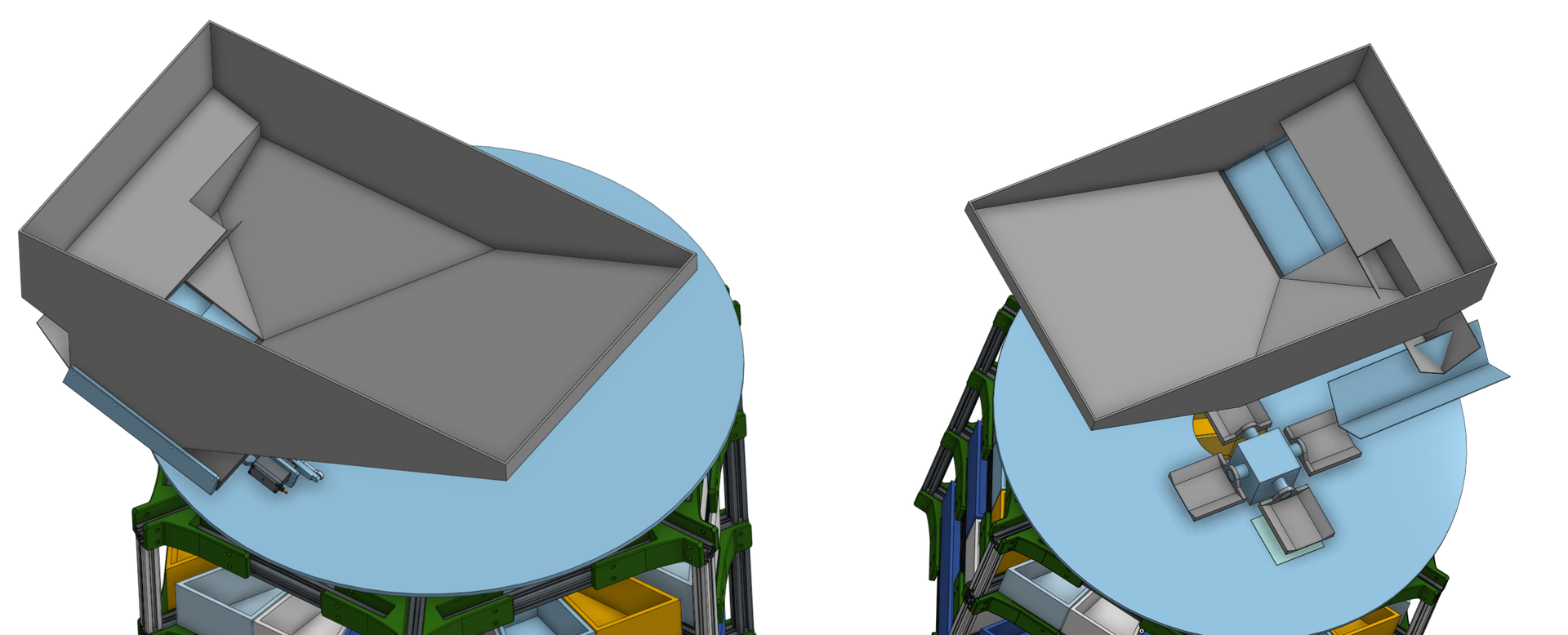

The design features circles of bins which are stacked on top of each other. A rotating chute in the middle catches pieces as they fall and diverts them into an array of bins through trap doors. This would complete the distribution system.

The feeder would then be mounted directly on top of the distribution system.

The benefits are crazy:

- There is no conveyor belt. Conveyor belts are difficult to maintain and set up.

- The previous design required at least one servo per bin. This requires only one servo per layer, which could have up to 18 bins on it, in addition to the single motor driving the entire chute.

- The distribution speed is constant. It takes a long time to send a piece down a conveyor belt, but in this version, the piece only needs to drop at the speed of gravity down the chute.

- Modularity is simple. We can just add more layers.

- Bin sizes can be varied.

- It is very dense.

The frame is going to be made of 2020 aluminum extrusion. The bins are going to be laser-cut from cardboard, and the rest is going to be 3D printed.

Piece Size Constraints

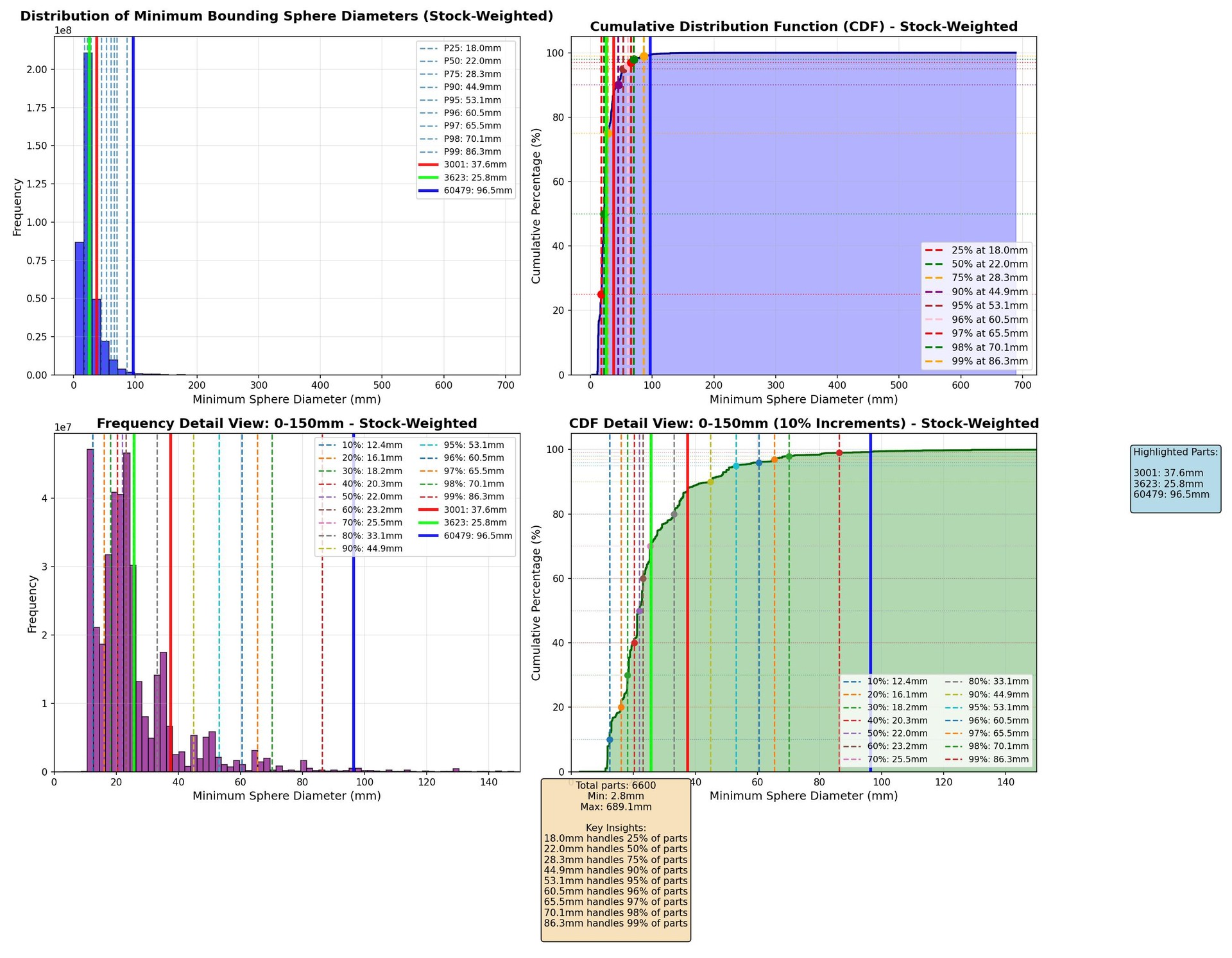

Every design has some maximum piece size it can support. In the circular design, that's defined by the throat where pieces enter the bins.

The naive lens through which we first decided to think about this problem is with a sphere. Imagine the minimum sized sphere that every piece we want to support fits inside of, such that the sphere can roll through the entire system. If it can, then none of those pieces can jam it.

Using a dataset scraped off of Bricklink, we got a glimpse of the exact distribution of pieces that are for sale all around the world, which should be pretty representative of the LEGO® pieces that are in people's bins all around the world. An 80mm diameter sphere captures well over 98% of all the LEGO® pieces in production.

Conveniently, pieces bigger than that are easy to manually sift out.

The Feeder

Or the singulator. I don't know, I've gotten corrected by a lot of people, but I've referred to it as the feeder too many times now.

The feeder is notoriously the most difficult part of building a LEGO® sorting machine. And to increase the stakes even further, we're effectively bundling it with classification.

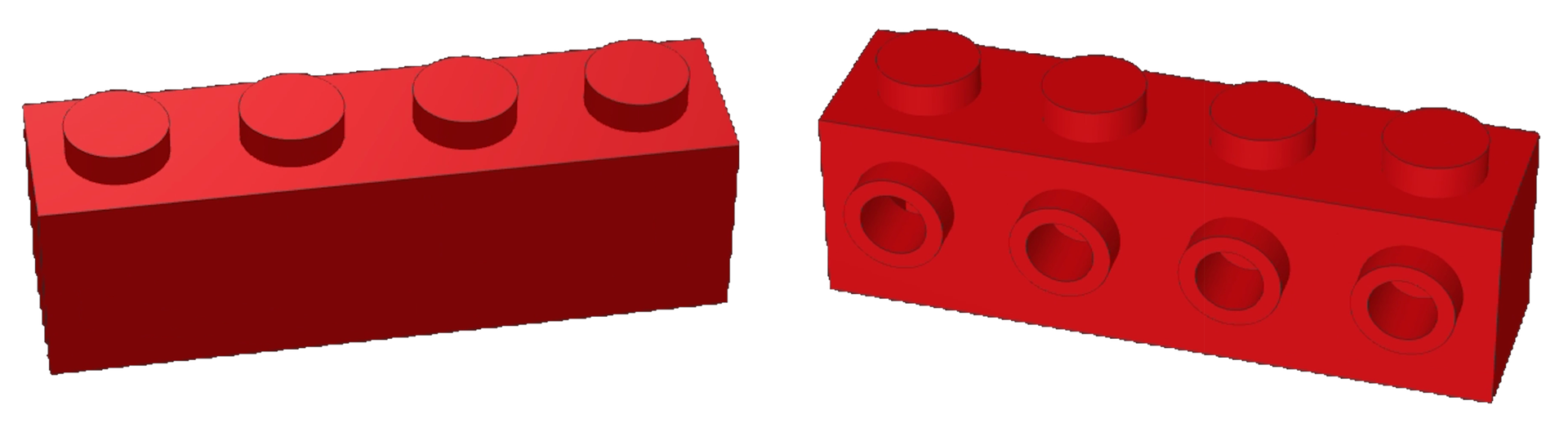

The Obfuscation Problem

One major handicap from V1 that I never covered was the problem of obfuscation. Depending on the way that a piece is oriented, it can be unclear exactly what it is. For example, is this a 1x4 brick, or is this a 1x4 brick with studs on the side? We need to see more angles.

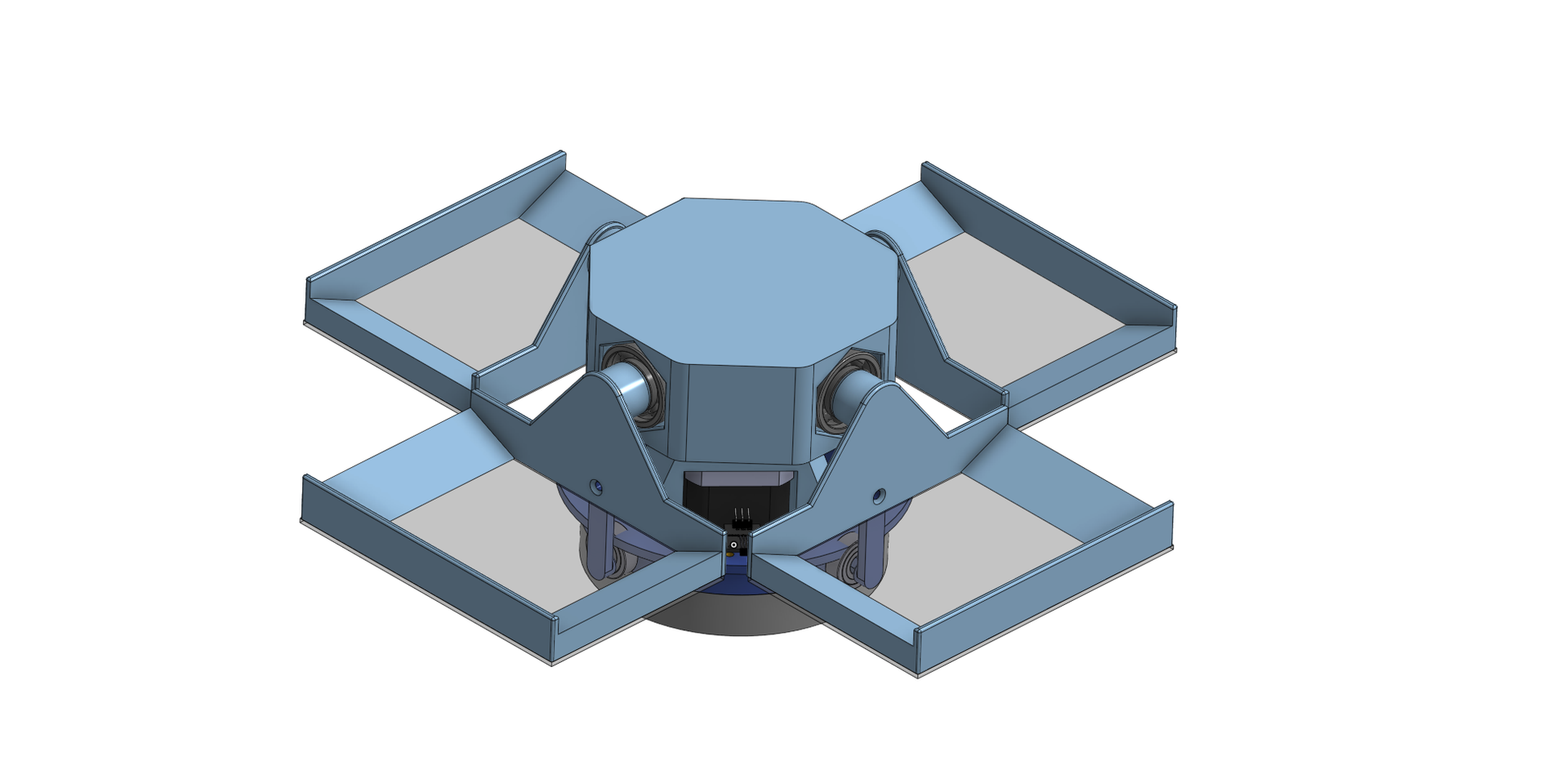

From Conveyor to Carousel

As I mentioned earlier, conveyors suck. They're difficult to maintain, struggle with round pieces, and require clear belts to solve the obfuscation problem. Running multiple pieces in parallel demands sophisticated mechanisms and software. For a kit that needs to be user-friendly, all this complexity would be a setup nightmare. This drove us to eliminate them entirely.

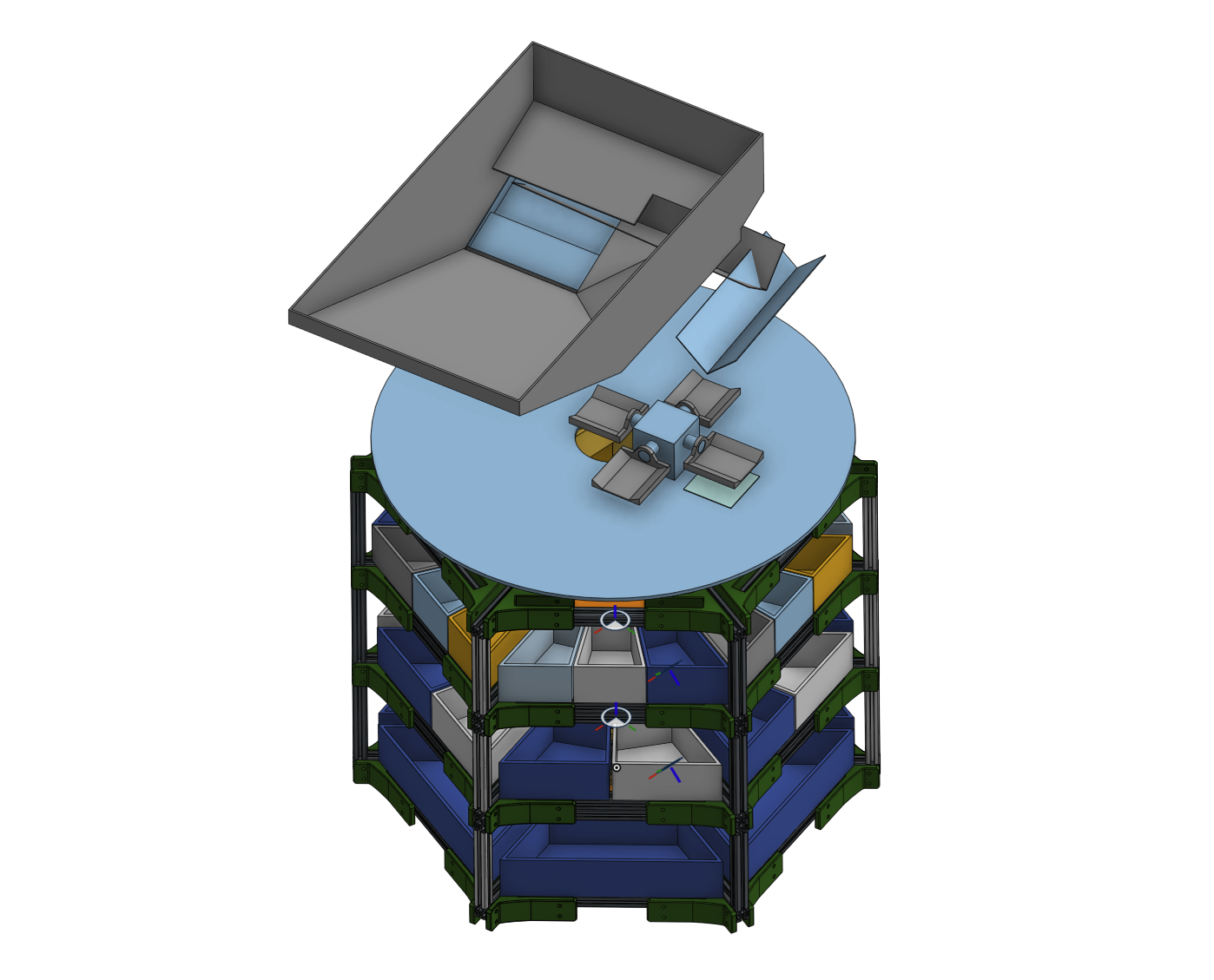

And because he also hates conveyors, Tom Hillen, the project lead on the feeder, introduced his idea for the carousel.

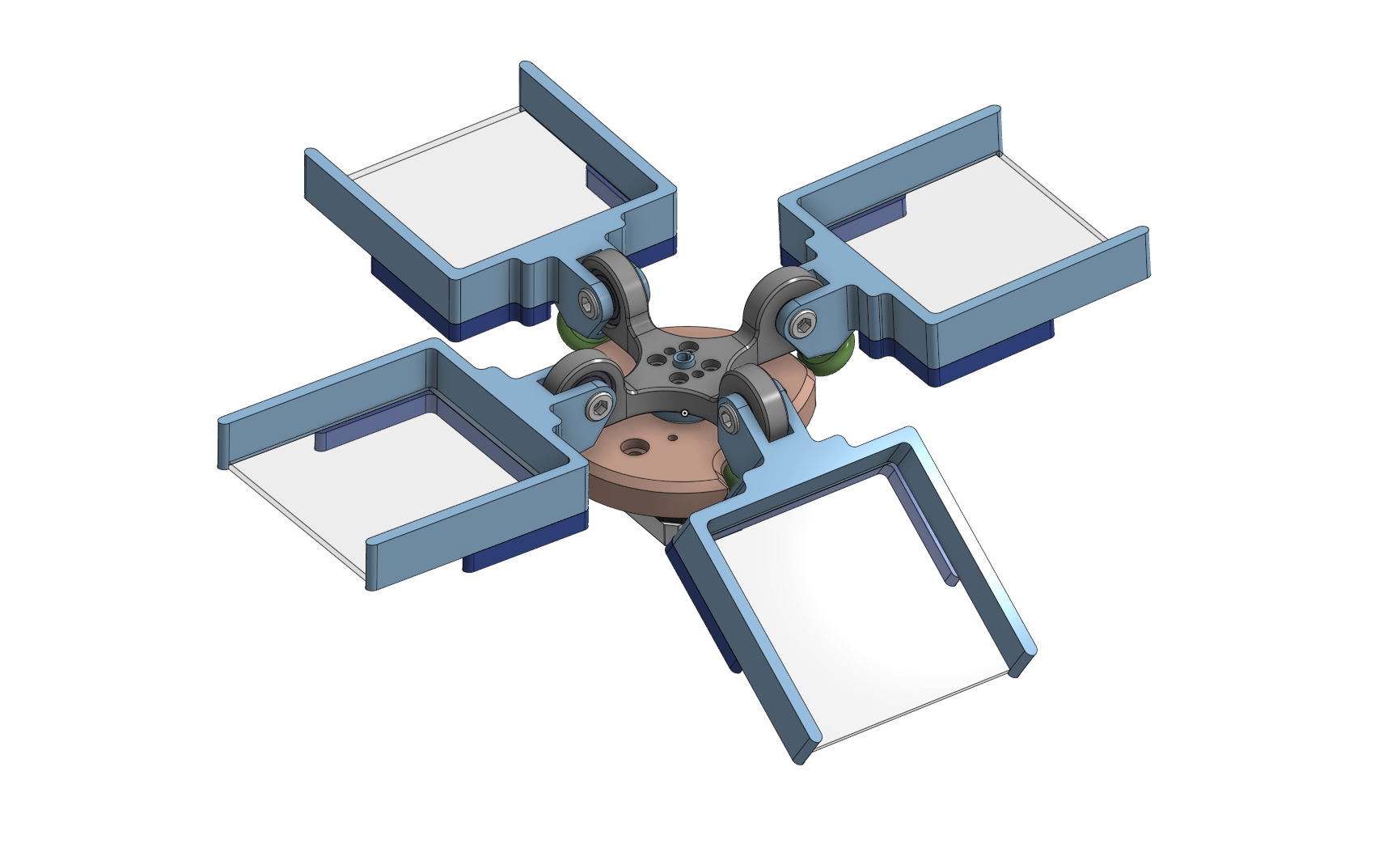

It features four rotating platforms with acrylic bottoms so that we can place multiple cameras, or mirrors, to get every angle of a piece. This also allows us to parallelize the work a lot. While we are feeding on the first platform, we can be taking a picture on the second, processing that image on the third, and dropping it on the fourth platform. And so theoretically all the platforms have a piece on them at the same time. What's neat is that this entire system is accomplished mechanically, so we only need one motor at the center.

The Outward Tilt Solution

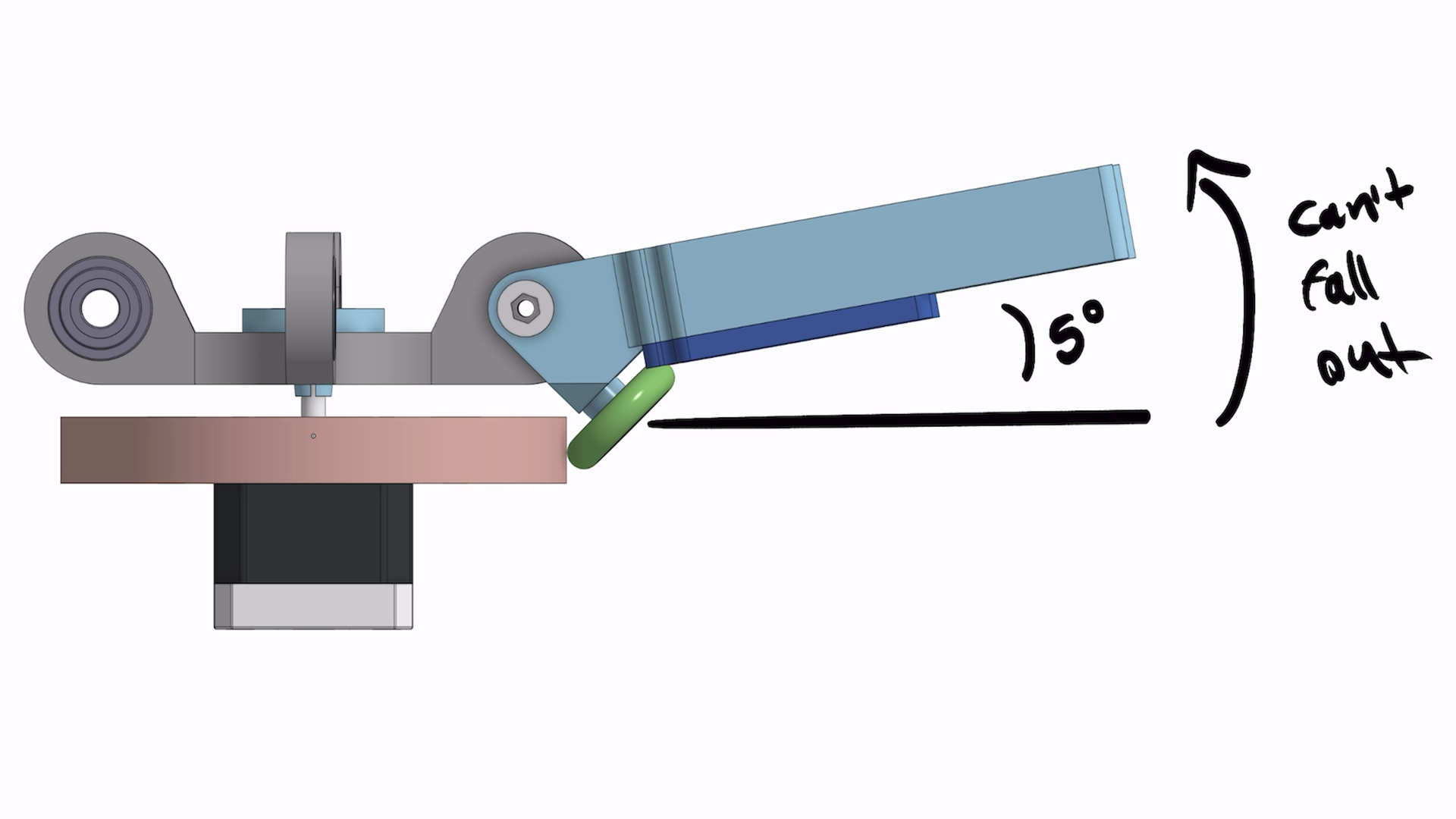

The original design featured bins that rotated parallel to the direction of rotation. One major issue we found was that pieces would get stuck on the lip at the end of the glass, and it wasn't obvious how we would fix that. Jose presented this design where bins tilt outward, perpendicular to their rotation.

This is nice, but this introduces another issue where pieces will want to fling out of the tray due to the centripetal force. To fix that, we just tilt the trays up a little bit.

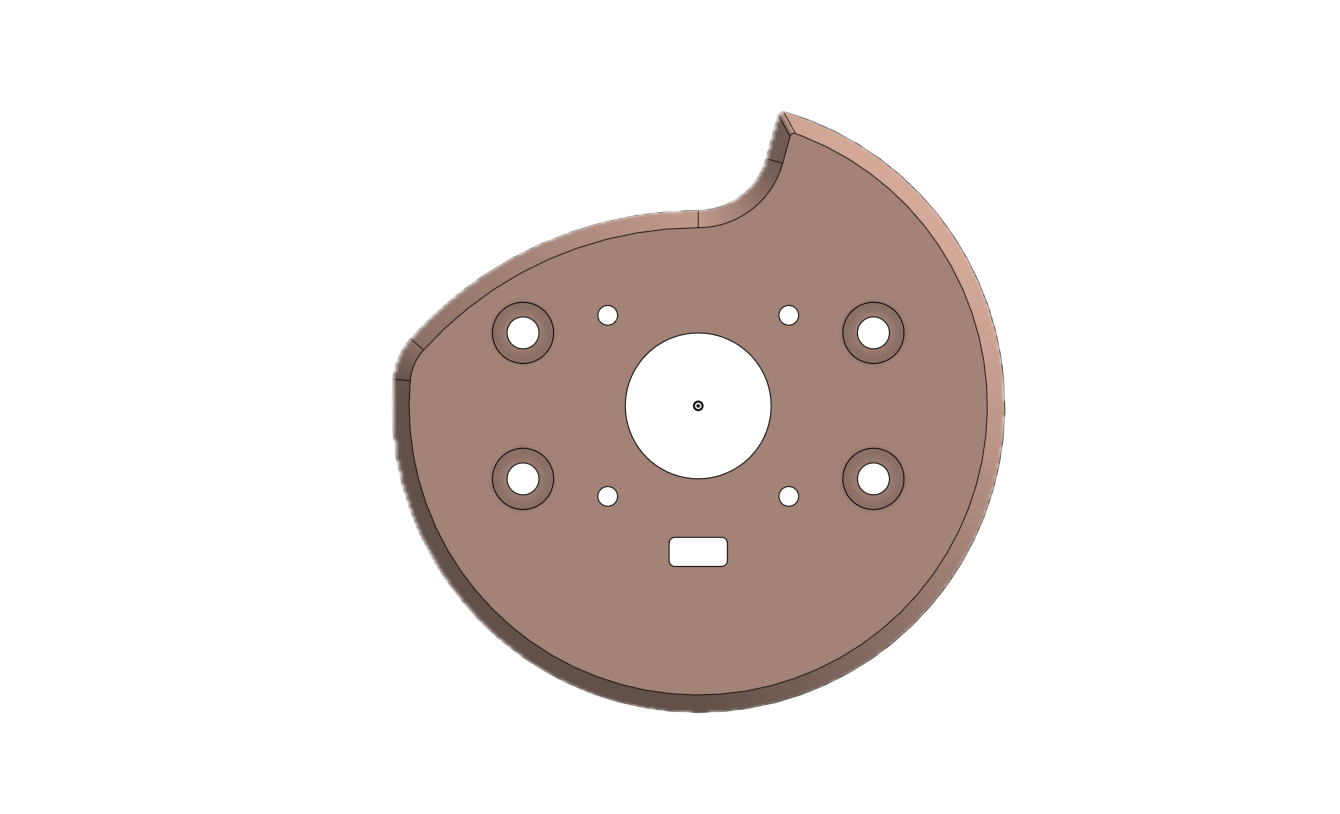

All of this motion is defined by this neat cam at the core.

The Bulk Bucket

Finally, to end our war against conveyors, we've decided to remove the conveyor from the Bulk Bucket in version one. We've decided to use a step feeder, which if oriented correctly, should support every piece that we want the machine to support without the complexity of a conveyor belt.

What's Next

The next step, of course, is to bring all of this into the real world. Entire new categories of issues are revealed when CAD enters reality. There is a lot of really clever engineering happening all across this project in the electrical, software, and mechanical spaces that I didn't get to cover yet in this post.

If you're interested in getting involved from an engineering perspective, you can check out the Discord here. If you're interested in news about the project and its future development, please fill out this form.